The sake industry is at something of a crossroads. Although there has never been a better time to drink sake, the industry is still struggling. While there is an increase in the consumption of tokutei meishoshu (higher grade sake) the downturn in lower grades drags down the overall national consumption. Nihonshu is still losing out to shochu and consumption of wine and craft beer is increasing in leaps and bounds. But all is not lost. Far from it. The new guard of sake brewers are doing some amazing work in bringing sake into its new era. An era where old school brewing methods and throwbacks to sake styles that fell by the wayside after the “ginjo boom” of the eighties are seeing are resurgence as the makers themselves reach for a new audience that will hopefully keep the industry alive and see it thrive into the future.

Among this new guard of sake brewers is Hashimoto-san of Miyoshino Jozo, brewer of Hanatomoe. Located by the Yoshino river in the ancient capital of Nara, Miyoshino Jozo is surrounded by timber yards trading in the local Yoshino cedar for which the area is renowned. For a brewery that only produces around 200 koku per year (36,000 litres) the building itself is surprisingly large. However up until only a few years ago Miyoshino Shuzo was producing up to 1800 koku (324,000 litres). The sake being produced though was sold off under the now all but defunct oke-uri (tank selling) system where small breweries produced sake to set specifications to be sold off to the big boy breweries where the sake was labelled as their own. A practice that seems pointless but it guaranteed that sake produced would be sold and also sake sold this way was not taxed by the government, making it a clever business strategy for many smaller breweries. As overall consumption of sake declined though, the larger breweries no longer needed to outsource to these smaller breweries and the mutual back-scratching was over. Miyoshino had always produced Hanatomoe on the side but it was only a few years ago that Teruaki Hashimoto stepped up to take control of the family business and set them on a path that has seen the rebirth of Hanatomoe as a sake of character, body and a true sense of place.

After graduating from Tokyo Agricultural University, Hashimoto-san learned the sake brewing trade at the shrouded in mystery Kenbishi. Although Kenbishi is one of the largest breweries in the country they are known as much for their secretive brewing methods as they are for their bold, full bodied sake. All their sake is made in the yamahai method of slow fermentation and they also use in-house yeast. “In-house yeast” as in natural airborne as opposed to cultivated yeasts used by most breweries. This style of production appealed to Hashimoto-san and these two production principles are the foundation for the Hanatomoe character. When Hashimoto-san returned to the family business he convinced his father to do away with the Hanatomoe of old. The brewing team had always been a team of hired guns that came only during the winter brewing season and as the oke-uri system was no longer particularly profitable the decision was made to scrap it all together and let Hashimoto-san start again from scratch. By himself.

In his first year Hashimoto-san produced only 80 koku. A size-able decrease from the 1800 koku produced 10 years earlier. Still, 80 koku is a lot for one person. Increasing year by year now to 200 koku, Hashimoto-san is aiming for 500-600 koku. At a time where many brewers lament that they’re maxed out and couldn’t brew any more if they wanted to, 36 year old Hashimoto-san’s youthful optimism and drive is inspiring. Equally impressive is his ability to embrace old-school brewing methods without being chained by tradition. Hashimoto-san’s determination to make the sake he wants to make ie. sake to be drunk with food, with character and acid is proving to be the type of sake many modern drinkers are looking for.

One of the first things I noticed about the brewery is the size. It’s definitely set up to brew much more sake than is being currently produced. The surplus of tanks however, works in the brewery’s favour as it means there is no rush to free up tank space in order to brew the next batch. In a brewery where the time consuming yamahai method is king, this is indeed a bonus. Also, Hashimoto-san likes to have the brewery ready to brew the 600 koku he is aiming to reach in the next five or six years. Although yamahai sake does involve the use of natural airborne bacteria to create the lactic acid that is required for a sanitary fermentation, most breweries use yeast that is cultivated or even “store bought”. Hashimoto-san reasons that sake of old was produced using airborne yeasts and that seemed to work out alright for everyone then so why not bring it back? Many brewers would claim the inconsistency and the potential for unwanted bacteria to throw of the sake be a fair enough reason but Hashimoto-san is not swayed. Even if there is something of a variance in his sake from year to year it’s still his sake. He compares it to someone who maybe loses or gains weight from year to year. “They might have a different body but they’ve still got the same face, it’s still the same person” he reasons. His acceptance of possible variance is also apparent in that he keeps up to five or six starter mash tanks altogether in the same room right next to each other. This leaves the potential for some of those natural yeasts to jump from one tank to the next which may contain a cultivated yeast and vice versa. A practice Hashimoto-san acknowledges some toji would deem unthinkable. “If it happens, I work with it and that becomes the character of that sake”. Hashimoto-san is nothing if not adaptable! “It all happens in here so it’s all an indigenous reflection of our brewery,” he calmly explains. Rather than the character of the water used, or the origin of the rice this is indeed a true expression of irreplicable terroir. The character of the brewery rather than the region itself is what many consider the answer to the question of whether sake has terroir. There is also a reflection of the brewery location in Hanatomoe sake. Much of the rice used is contract grown, local rice, and some of that rice is also organic. The organic rice is grown in the simple way of introducing wing-clipped aigamo (a breed of duck) into the rice fields. The ducks live there for the harvest season eating all the bugs and pests keeping the rice clean and pesticides unnecessary. The other hint to Hanatomoe’s locale is the use of the Bodai-moto (also known as Mizu-moto) method.

The Bodai-moto method has its roots in the Kamakura Period, around 1200AD. At this time Nara was one of the leading areas of sake production. Brewing was largely conducted by monks in temples as sake was still more of a ceremonial than social drink. Many of the basic sake production methods still used today were founded by these monks and one discovery, by the monks of the Bodaisen mountains, was the Bodai-moto method. To simplify, this method involved starting with raw rice and water which when left would produce a lactic acid thanks to naturally occurring bacteria. In the traditional Bodai style, steamed rice would usually then be added to the mix but Hashimoto-san skips the steamed rice an leaves the mix for a week producing a highly pungent acidic starter. Then, the raw rice is removed and steamed before being returned to the lactic acid-rich water (soyashi mizu) where koji is also added. Again here, Hashimoto-san relies on naturally occurring yeast to get things started in what is a fairly time consuming process taking up to 40 days or so before being ready. This method of creating the starter mash is rarely used anywhere other than Nara, in fact Nara is home to the Bodai Moto Resarch Centre which works to keep the method alive. When I visited the brewery I was fortunate enough to see a tank of Bodai-moto (a wooden tank incidentally) bubbling away. In comparison to the often sweet, banana aromas of regular starter batches, the Bodai was noticeably pungent and rich with a funky edge to it. Very enticing!

But not everything at Miyoshino Jozo is old school. For example, among all these old school methods it was very surprising to see that unlike just about every brewery I’ve ever seen, koji mold is not propagated onto the rice by hand. It’s not uncommon to find photos of brewers ever so carefully sprinkling their magic koji powder with a mesh covered cup-like tool onto steamed rice in the koji room. Every brewer having their own particular style of applying the mold. But always by hand. Like most breweries, after the rice is steamed it passes along a conveyor belt where it is then taken to the koji room or to the tanks as the case may be. At Miyoshino-Jozo there is a koji applicator machine at the end of the conveyor belt that the rice passes through, receiving a dose of koji powder as it does. This machine provides a thorough and even application that works well with the Hanatomoe style of koji-heavy body, so Hashimoto-san sees no reason not to employ such technology. Again on the flip-side, whereas many breweries use all sorts of machines, gauges and gadgets to determine when a sake or a yeast starter is ready Hashimoto-san relies on his senses. In fact the whole brewery has a noticeable lack of data, graphs and figures often spotted at other breweries. Again, as Hashimoto-san works almost entirely by himself he explains that as long as he knows what’s going on there’s not much need for data to be pasted all over the walls.

Hanatomoe sake can basically be divided into two categories, the kanji label 花巴 and the hiragana label はなともえ. All sake produced under the kanji label, regardless of grade is made with natural occurring yeasts in either yamahai or bodai style. All sake under the hiragana label is made with cultivated yeast, predominantly the fragrant ginjo-esque no.9 yeast. Simplistically speaking the hiragana label sake tends to be fruitier and lighter. Most of this sake is somewhat fresh, vibrant and juicy. The sake under the kanji label is arguably the real Hanatomoe. Full bodied, rich koji-rice driven aromatics, broad sweetness with a tangy acidic mouth-feel and grit that belies the natural soft Yuzuriha water used in the brewing process.

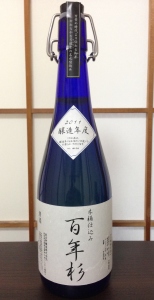

On top of these standard staples of the Hanatomoe line-up I was intrigued by some of the cellar door offerings available. Hashimoto-san is a keen experimenter and one of his pet projects is his 100 Year Cedar (hyakunen sugi) barrel production sake. Being surrounded by timber yards in the middle of the Yoshino cedar timber industry, using the local cedar barrels to ferment sake seemed the next logical step in demonstrating the terroir of the area. Most sake these days is produced in enamel coated tanks which offer a far more sanitary environment as opposed to wood which fungus and bacteria tend to linger in regardless of cleaning. Again, Hashimoto-san sees this as just another character trait to the Hanatomoe sake personality. The sake is also aged on site in the bottle so various vintages are available if purchased direct from the brewery. The 2011 was my pick of the bunch. A tangy aroma of mandarin rind leading to a tight, acidic, slightly sweet and lighter than expected body. Peppery hints of cedar influence are present but far from dominating.

Another treat only available direct from the brewery is their 100% Organic Nansen Aged sake. Made using rice from the aforementioned aigamo fields in the yamahai style with natural occurring yeast, this is totally hands-off sake brewing. Subtle honey notes lead softer hints of rice and an astringent but sweet, viscous body. An after-dinner sake of depth that would be fantastic with some dried fruits and soft cheese.

So, as the sake industry sits at this crossroads where some breweries are struggling to find an audience in this new world environment, it’s exciting to see breweries like Hanatomoe. With a clear vision of what he wants to achieve Hashimoto-san is setting the bar high in terms of producing new world sake that respects the traditions of brewing with just the right amount of rule bending and experimentation. This could be just the right combination that sees sake reach that new audience it needs and drags it back into center stage where we all know it belongs. Exciting times!

Leave a comment